Like a cage in search of a bird, Ai Weiwei locks the Singaporean film-goer in 2 hours of cinema-turned-refugee-camp in his experiential film, a hymn to life in an unlivable world.

By Tan Jing Ling

There is a sublime beauty to Human Flow in how it depicts space, freedom and movement. But it is a beauty that I cannot bear to swallow.

For a country whose borders have been closed to refugees since 1996, Human Flow is a passport to places even the Singaporean passport cannot access. Shot across 20 countries, Ai brings to the big screen a tragedy that the world has closed its eyes to: the global refugee crisis.

Human Flow opened in theatres in 2017, at a time when many parts of the world were rapidly closing doors on refugees. All art is political, and this documentary film by artist and political activist Ai, is as much an aesthetic production as it is a political statement. To make art out of tragedy seems cruel, but it is one way to breathe life into a dying crisis.

And breathe it did into the air of The Projector’s Redrum theatre, as the 145-minute film closes the gap between my privileged-air-conditioned-Singaporean-cinema-seat and the atrocities that refugees face. Brought face to face with individuals who lived on deaths, with homes built on dust, and with camps full of scarcity, Ai portrays things just as there are: inhumane.

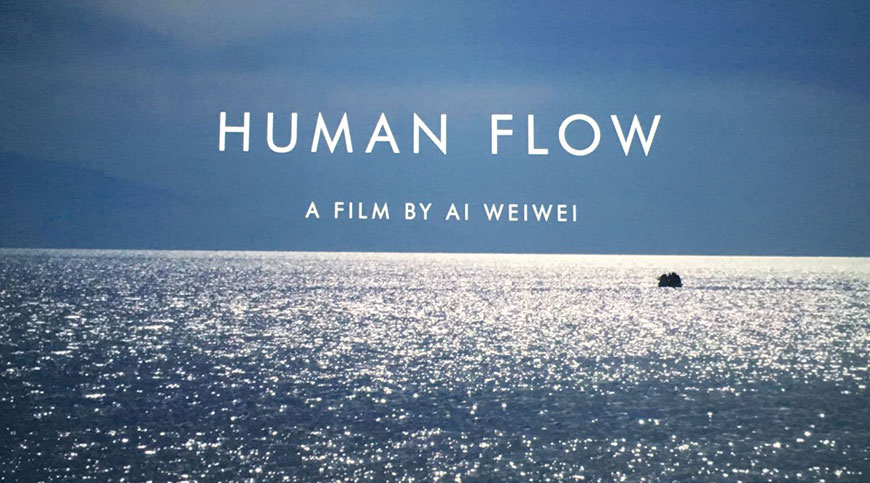

The film opens with a wide-angle shot of a rubber boat at sea, crammed to each centimeter by orange lifejackets wrapped over touching bodies. This references Ai’s earlier art installations about the refugee crisis: Reframe which wrapped Florence’s Palazzo Strozzi in rubber rafts, as well as Law of the Journey, a massive lifeboat installation in Prague.

Above the surface of the sea, the first words of the film are unspoken: “I want the right of life, of the leopard at the spring, of the seed splitting open – I want the right of the first man.” Ai is quoting Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet’s Hymn to life.

It is through quotes like this that Ai makes his moral and political stance apparent in the otherwise speech-deprived film. Rarely does a film speak so much by saying so little. Except for the interviews conducted, Ai’s world is short of words but extensive in imagery. Ai sets the audience on an uncomfortable journey, with nothing but pithy quotes from poems and media article headlines to navigate one’s way.

The lack of a narrative proper makes the lengthy film hard to follow. Switching back and forth between many different countries, Ai leaves the audience lost and disoriented. Yet, that is the point: the film is not about refugees, but about us in safe harbours, being unable to comprehend the sheer torment of being a refugee; us making policies and decisions that we would never subject ourselves to.

This is Ai’s subtext: being a refugee means losing, amongst all things, control of one’s narrative. To watch human flow is to experience what it is like to be a refugee – a stark contrast to the clearly defined narrative and privileges of being a Singaporean.

This, two hours of experiential film, is more than enough to reduce the audience to silence, gasps and tears, yet it can hardly be compared to the eternal agony refugees experience. Two hours of emotional turmoil for film-goers is to refugees a permanent reality, 24/7, 52 weeks a year, for an average of 26 years.

Such arresting statistics and media headlines punch the audience in the moral gut each time they appear onscreen. The New York Times photoessay “The Migrant Crisis, No End in Sight” was accompanied by literal scenes of families walking arduously from nowhere, to nowhere. Ai’s use of poetry, headlines and statistics, across centuries and across countries, proves that ‘human flow’ is a perennial problem, one that we can read of and measure, but choose to disregard.

Yet, it is not the statistics that hurt, but the individual stories. One scene shows Ai interviewing a refugee woman, seated with her back facing the camera, shaken to a puking ball of tears when asked seemingly ordinary questions about her life. Another scene shows a man weeping at a cemetery, with nothing but a few photos left of his loved ones who were drowned by the journeys they made across the seas. While the film relies on Ai’s cinematographic choices to capture the tragedy of movement, it is these raw stories that depict the reality of being a refugee.

Unlike other visual documentary films like Ron Fricke’s Samsara, Ai does not detach himself from his subjects. Ai features himself in several scenes interacting with refugees or filming in the background. One scene shows Ai temporarily exchanging passports with a refugee, with Ai saying: “I respect you and I respect your passport.”

Ai’s inability to detach makes the film contentious: is the film really about the refugee crisis, or is it about Ai’s role in the refugee crisis? Does Ai treat refugees as objects of his aesthetic endeavor, or as dignified human subjects? Is Ai, from drone shots to close-ups, too far from understanding, or too close for comfort?

There are many other ways to read the film: there’s Ai’s position as a political refugee of China and his identity vis-a-vis the refugees in his film. There’s also the shared oppression of animals and refugees, with caged birds and a Palestinian tiger who lost her home. The space and distance between refugees and countries, between refugees and freedom, between refugees and the audience. There are many possible conclusions to draw from such a film with a loose narrative and grandiose intentions. Regardless, Ai has created a film that once seen, cannot be unseen, and transcends ideological and geopolitical borders.

With a sold-out show and panel discussion for the film held during Singapore’s Refugee Awareness Week 2018, the refugee crisis seems to have reached the shores of Singapore in spite of its closed borders. One drop at a time.

As Ai aptly invokes from the Dhammapada in the film:

Neither in the sky nor in mid-ocean,

nor by entering into mountain clefts,

nowhere in the world is there a place

where one may escape from the results of evil deeds.

Ai Weiwei’s Human Flow will be screened in Singapore at The Projector on 22 July and 25 July. For tickets and more information, click here.

Tan Jing Ling is an undergraduate of Sciences Po and the National University of Singapore, majoring in social science and political science. He has been volunteering with the Advocates for Refugees – Singapore (AFR-SG) since 2017 and was in the working committee of Refugee Awareness Week 2018. In his free time, Jing Ling enjoys films and local theatre, and occasionally writes reviews about them if he gathers the will to.