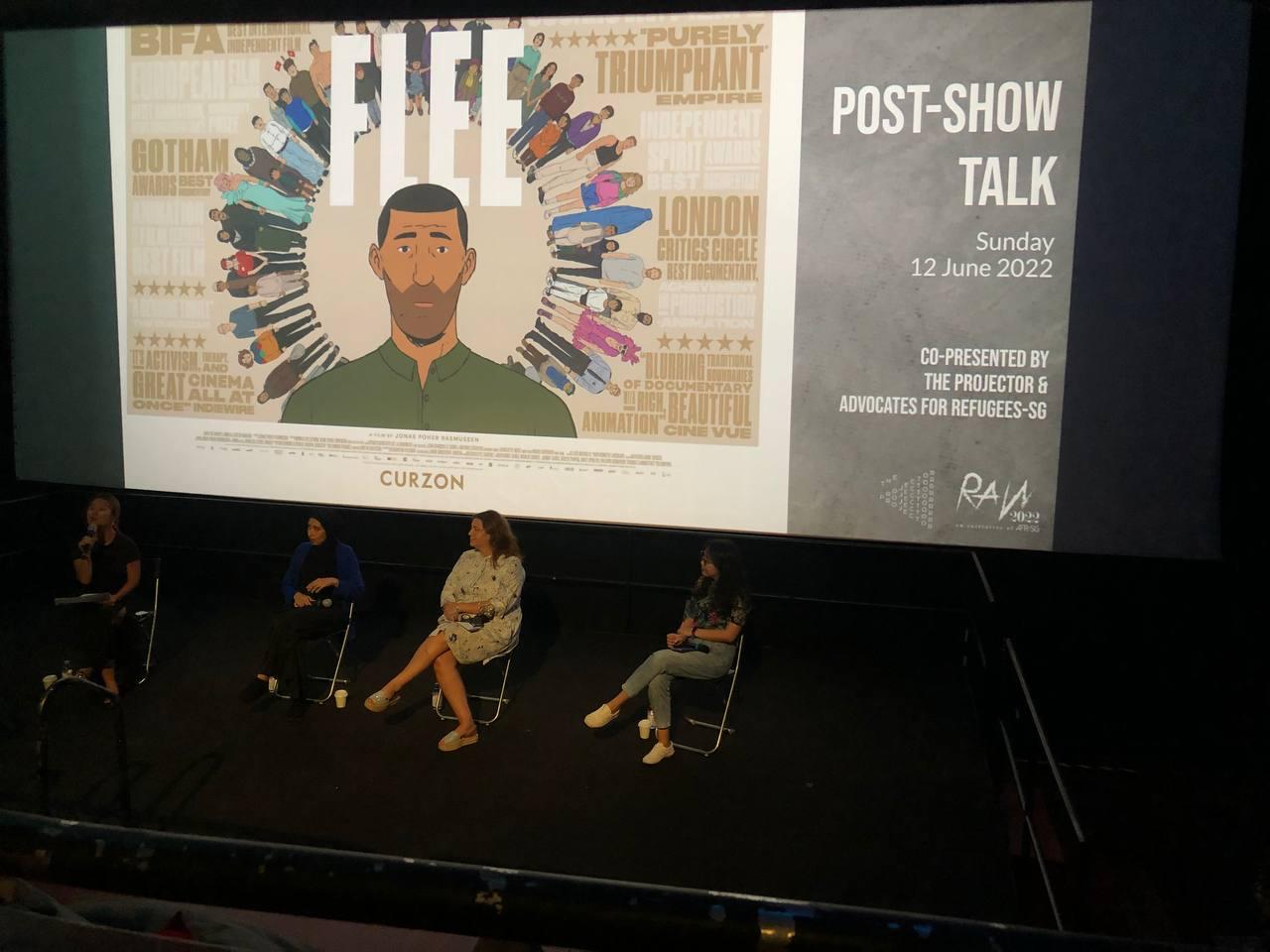

On 12 June, Advocates For Refugees – Singapore (AFR-SG) partnered with local cinema The Projector to screen Flee, a film recounting the true story of Amin, a gay Afghan refugee who fled Afghanistan following the 1989 civil war. Amin’s experience of stigma, shame and trauma at the intersection of two marginalised identities provided ample food for thought on the realities of living beyond the margins and the enduring commonalities that tie us as humankind.

by Amanda Chen

These topics were dissected in our post-show dialogue featuring Dr Gül İnanç, founder of Opening Universities for Refugees and founding co-director of the Centre for Asia Pacific Refugee Studies, Dr Hana Alhadad, a trauma-informed consultant and researcher with extensive experience working with migrant communities, and Ms Mathilda Ho, founder of AFR-SG and Deputy Chair for the Southeast Asia Working Group at the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network. The dialogue was moderated by Ms Selene Ong, a volunteer of AFR-SG.

To kick off the dialogue, attendees were invited to respond to the question, “What is the first thing that comes to your mind when you hear ‘human identity’?”

Dr Gül elaborated on the concept of human identity as being complex and shifting in nature. She highlighted that different labels can be assigned to one population, each with their own definitions which may have specific implications in formal contexts; examples include ‘forcibly displaced’, ‘stateless’ and ‘refugee’. These labels and their accompanying legal criteria may overshadow the humanity — the unique perspectives and experiences — of the people bearing them. Dr Gül noted that we can refer to the responses given by the audience, including ‘freedom’, ‘belonging’, ‘acceptance’ and ‘dignity’, to understand what connects us as humans. While the parts of our lives that we, or others, pin as our identity may always be subject to change, our striving towards a fundamental set of needs underlies the shared human experience.

Dr Hana expanded on the centrality of belonging to human identity. More than simply being included in a community, which may be predicated on changing parts of oneself to fit the expectations of the group, belonging implies unconditional acceptance. This freedom for people to be themselves completely, knowing that they will be accepted as they are, can be seen as a fundamental human need, but also as a privilege that not everyone enjoys.

Addressing a question from the audience on whether belonging exists on a spectrum, Dr Hana noted that we each have many intersecting identities and may find ourselves ‘belonging’ to some communities, such as our home, more fully and naturally than others, such as our workplace. Adding to the notion that human identity is rooted in how we see ourselves in relation to others, Mathilda highlighted the importance of connecting with others on a personal level. In particular, real interaction is essential for us to accurately understand the perspectives of other people and to perceive them as they are, rather than as they tend to be portrayed in popular media.

As the topic of discussion progressed to our attitudes towards people marginalised by society, a question from the audience probed whether asylum seekers must portray themselves as “model” refugees in order to be granted asylum, and whether this bar is set too high. Dr Gül recalled her encounter with the term ‘first class refugee’ in Malaysia — this referred to someone with education, money and proper identity documents, often from a Middle Eastern country such as Syria.

In contrast, others such as Rohingya refugees from Myanmar were treated as inferior. This highlights how differential treatment exists even within marginalised groups, depending on how different aspects of identity such as ethnicity and class intersect within an individual. Dr Gül noted that guidelines for the recognition and treatment of refugees remain as those laid out in the 1951 Refugee Convention developed following World War II. Formal changes to make policies more inclusive, such as towards elderly refugees, and more flexible to accommodate unique challenges faced by refugees in different regional contexts, are yet to be enacted.

In parallel to the concept of ‘model refugees’, Selene noted how certain ‘attractive catastrophes’ tend to garner more attention and sympathy than others. Our recognition of important issues in the world tends to depend on the media and their perception of what stories appeal most to audiences. For instance, the spread of information regarding ongoing humanitarian crises in Africa or Yemen pales in comparison to that relating to the war between Ukraine and Russia. Dr Gül noted that crises are experienced at an individual level, varying in degree depending on the specific contexts that people find themselves in; the framing of longstanding phenomena like migration as crises to nation-states is much more debatable.

Dr Gül further pointed out that pejorative labels such as ‘boat people’ and ‘illegal migrants’, popularised by media narratives, unfairly strip refugees of their humanity when after all, in her words, “actions can be illegal, people can’t”.

An audience member posed the question of whether we should focus on extending compassion to those in need in our backyard, or in communities distant from us — both Dr Hana and Dr Gül felt a strong responsibility to do both.

Taking a holistic view of the issue of forced displacement, the panelists also considered perspectives of other stakeholders involved. In response to an audience member’s question on managing the tension between the “scammy and dangerous” nature of trafficking journeys and the imperative on refugees to make these journeys due to their lack of alternatives, Dr Hana shared observations from interactions with human traffickers in her work. Some viewed themselves as saviours offering refugees a lifeline in desperate circumstances, some came from refugee backgrounds themselves and earnestly tried to find policy loopholes to get refugees to their destinations, others were exploitative and operated for the purpose of profit. Despite the ostensibly good intentions of certain traffickers, the danger that refugees are exposed to as a result of illicit journeys remains unchanged. Mathilda emphasised that this concept of irregular or illegal movement, allowing traffickers to exploit migrants’ journeys for monetary gain, only persists due to policies that make ‘legal’ journeys impossible in the first place. Acknowledging them as the basis of the desperate decisions that refugees are forced to make is perhaps the first step to alleviating their suffering that results.

Another question from the audience considered potential costs to the majority when marginalised groups are accepted into a community. This is salient in Singapore, which lacks geographical space to accommodate refugees — yet, Mathilda pointed out that our drive to expand economically has seen land reclamation efforts repeatedly come to fruition over several decades.

A lack of priority could hence be a stronger factor dissuading us from accommodating refugees compared to a lack of space. Selene added that as we readily enjoy the privilege of safety and belonging in our daily lives, we are responsible to share this privilege and uplift others who lack it.

At the end of the day, we are all simply humans, each with our own unique set of experiences and world-views. The documentary film ‘Flee’ offered an immersive insight into the world of an individual sidelined by society multiple times over, and the dialogue following it rounded our understanding of how we can support such individuals living life on the margins. To resist indifference and enact change, we can first and foremost respect each individual as the person that they are. As we forge connections and recognise the commonalities we share, the elements of life that make us feel human — belonging, acceptance, dignity and freedom — will follow.

Amanda Chen is a current BSc Neuroscience and Psychology student at King’s College London. She volunteers actively with organisations providing material and wellbeing support for refugees in the UK, as well as in northern France outside of term-time. Joining AFR-SG’s team for the first time in 2022, she is keen to learn more about the issue of forced displacement in the regional context and to do what she can to make a difference.

For more information about RAW 2022, please visit our platforms: